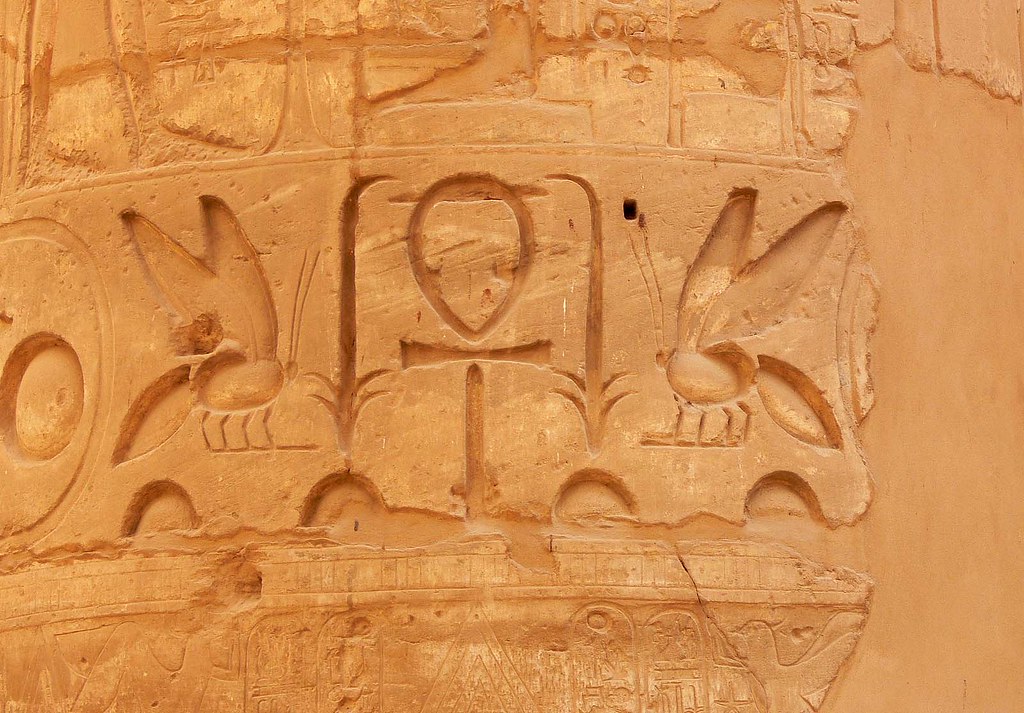

The Karnak temple complex, universally known only as Karnak, describes a vast conglomeration of ruined temples, chapels, pylons and other buildings. It is located near Luxor in Egypt. This was ancient Egyptian Ipet-isut ("The Most Selected of Places"), the main place of worship of the Theban Triad with Amun as its head, in the monumental city of Thebes. The complex retrieves its current name from the nearby and partly surrounding modern village of el-Karnak, some 2.5km north of Luxor.

The Karnak temple complex, universally known only as Karnak, describes a vast conglomeration of ruined temples, chapels, pylons and other buildings. It is located near Luxor in Egypt. This was ancient Egyptian Ipet-isut ("The Most Selected of Places"), the main place of worship of the Theban Triad with Amun as its head, in the monumental city of Thebes. The complex retrieves its current name from the nearby and partly surrounding modern village of el-Karnak, some 2.5km north of Luxor.The key difference between Karnak and most of the other temples and sites in Egypt is the length of time over which it was developed and used. Construction work began in the 16th century BC. Approximately thirty pharaohs contributed to the buildings, enabling it to reach a size, complexity, and diversity not seen elsewhere. Few of the individual features of Karnak are unique, but the size and number of features are overwhelming. Construction of temples started in the Middle Kingdom and continued through to Ptolemaic times.

The history of the Karnak complex is largely the history of Thebes. The city does not appear to have been of any significance before the Eleventh Dynasty, and any temple building here would have been relatively small and unimportant, with any shrines being dedicated to the early god of Thebes, Montu. The earliest artifact found in the area of the temple is a small, eight-side from the Eleventh Dynasty, which mentions Amun-Re.

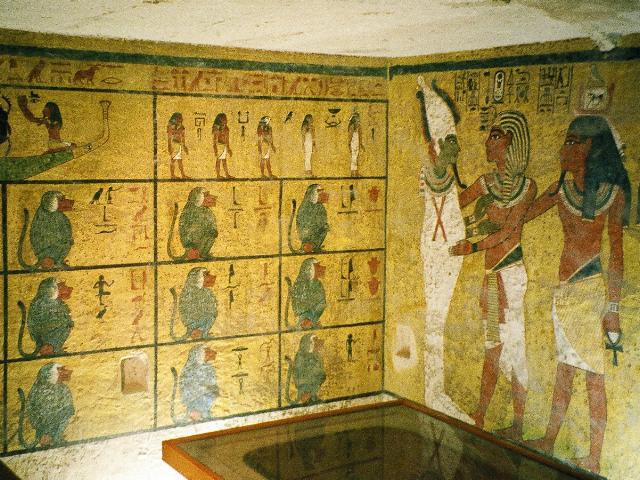

Major construction work in the Precinct of Amun-Re took place during the Eighteenth dynasty. Thutmose I erected an enclosure wall connecting the Fourth and Fifth pylons, which comprise the earliest part of the temple still standing in situ. Construction of the Hypostyle Hall may have also began during the eighteenth dynasty, though most building was undertaken under Seti I and Ramesses II. Merenptah commemorated his victories over the Sea Peoples on the walls of the Cachette Court, the start of the processional route to the Luxor Temple.

The last major change to Precinct of Amun-Re's layout was the addition of the first pylon and the massive enclosure walls that surround the whole Precinct, both constructed by Nectanebo I.

In 323 AD, Constantine the Great recognised the Christian religion, and in 356 ordered the closing of pagan temples throughout the empire. Karnak was by this time mostly abandoned, and Christian churches were founded amongst the ruins, the most famous example of this is the reuse of the Festival Hall of Thutmose III's central hall, were painted decorations of saints and Coptic inscriptions can still be seen.

Thebes’ exact placement was unknown in medieval Europe, though both Herodotus and Strabo give the exact location of Thebes and how long up the Nile one must travel to reach it. Maps of Egypt, based on the 2nd century Claudius Ptolemaeus' mammoth work Geographia, have been circling in Europe since the late 14th century, all of them showing Thebes’ (Diospolis) location. Despite this, several European authors of the 15th and 16th century who visited only Lower Egypt and published their travel accounts, like Joos van Ghistele or Andre Thevet, put Thebes in or close to Memphis.

The Karnak temple complex is first described by an unknown Venetian in 1589, though his account relates no name for the complex. This account, housed in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, is the first known European mention since ancient Greek and Roman writers of a whole range of monuments in Upper Egypt and Nubian, including Karnak, Luxor temple, Colossi of Memnon, Esna, Edfu, Kom Ombo, Philae and others.

Karnak ("Carnac") as a village name, and name of the complex, is first attested in 1668, when two capuchin missionary brothers Protais and Charles François d'Orléans travelled though the area. Protais’ writing about their travel was published by Melchisédech Thévenot (Relations de divers voyages curieux, 1670s-1696 editions) and Johann Michael Vansleb (The Present State of Egypt, 1678).

The first drawing of Karnak is found in Paul Lucas' travel account of 1704, (Voyage du Sieur paul Lucas au Levant). It is rather inaccurate, and can be quite confusing to modern eyes. Lucas travelled in Egypt during 1699-1703. The drawing shows a mixture of the Precinct of Amun-Re and the Precinct of Montu, based on a complex confined by the tree huge Ptolemaic gateways of Ptolemy III Euergetes / Ptolemy IV Philopator, and the massive 113m long, 43m high and 15m thick, first Pylon of the Precinct of Amun-Re.

Karnak was visited and described in succession by Claude Sicard and his travel companion Pierre Laurent Pincia (1718 and 1720-21), Granger (1731), Frederick Louis Norden (1737-38), Richard Pococke (1738), James Bruce (1769), Charles-Nicolas-Sigisbert Sonnini de Manoncourt (1777), William George Browne (1792-93), and finally by a number of scientists of the Napoleon expedition, including Vivant Denon, during 1798-1799. Claude-Étienne Savary describes the complex rather detailed in his work of 1785; especially in light that it is a fictional account of a pretended journey to Upper Egypt, composed out of information from other travellers. Savary did visit Lower Egypt in 1777-78, and published a work about that too.

credited to wikipedia and flickr users: joanot, twose, selva, jannet_duroc, xfp, merlin_1, sonofgroucho, juanj