Earlier this week, renowned NASA climate scientist James Hansen warned Congress of the dangers of climate change, exactly 20 years after he did so for the first time.

Earlier this week, renowned NASA climate scientist James Hansen warned Congress of the dangers of climate change, exactly 20 years after he did so for the first time. The message he delivered was almost the same as it was in 1988, but there was one key difference: "The difference is that now we have used up all slack in the schedule for actions needed to defuse the global warming time bomb," he said.

Hansen's message painted a stark and urgent picture of a world already past the point where significant damage would occur. Discovery News wanted to know if other scientists shared his view. Are we really in for it and at what point? What are our options for avoiding the worst?

Earth's Carbon Budget

Hansen argued this week that the "safe level of atmospheric carbon dioxide is no more than 350 ppm (parts per million), and it may be less." This recommended level is less than the amount currently in the atmosphere -- 385 ppm. It may also be less than the commonly discussed stabilization target of 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) of temperature increase, which probably corresponds to an atmospheric CO2 concentration of about 350-400 ppm.

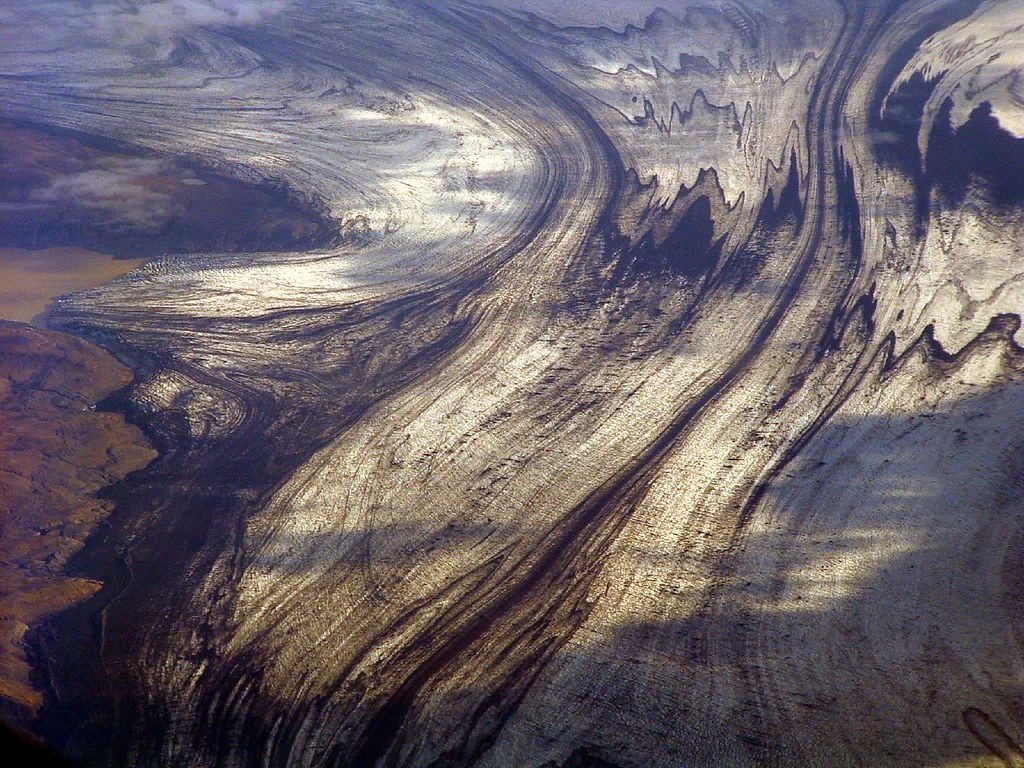

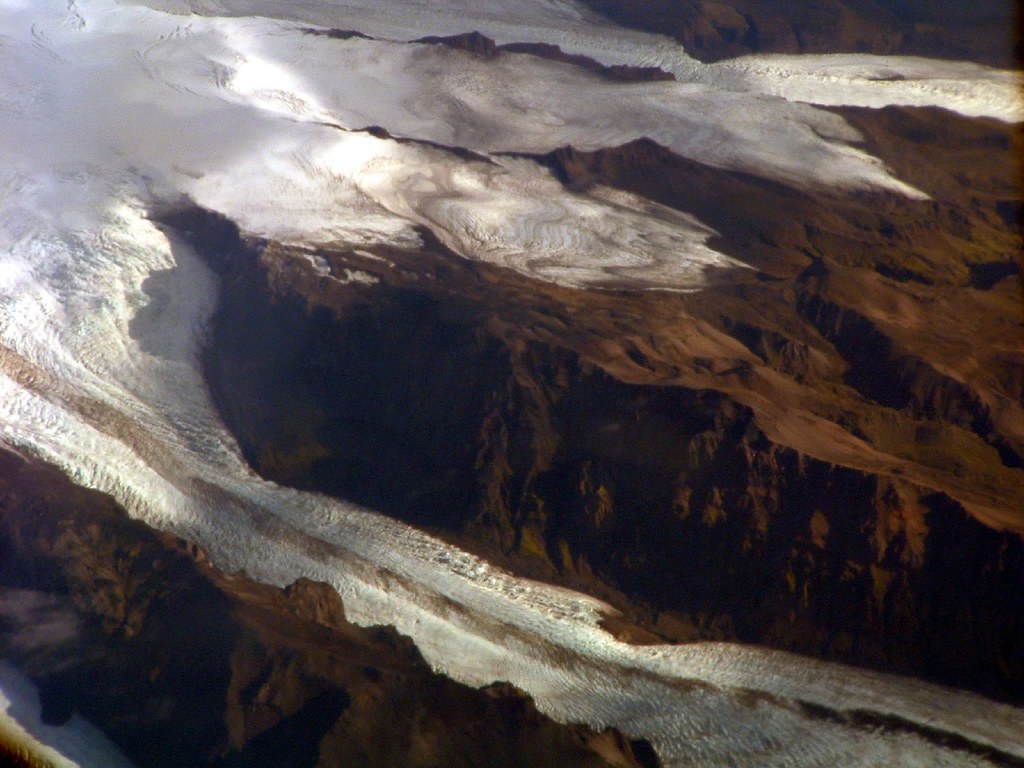

Already, he argued, arid lands are expanding, glaciers are receding, and Arctic sea ice is shrinking, driven by cycles of positive feedback, where melting leads to more warming of the exposed dark ocean water, which leads to more melting.

"As a result, without any additional greenhouse gases, the Arctic soon will be ice-free in the summer," Hansen said.

To forest ecologist Lee Frelich at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, Hansen's argument that a lower stabilization target is safer makes sense.

"If you look at the paleological record, in the last interglacial period 110,000 to 120,000 years ago, the world was thought to have a climate that was two degrees warmer than today," Frelich said. "The oceans were 20 to 25 feet higher, but CO2 was only 290 ppm. I've always thought that if a CO2 content of 290 could cause that, why won't it do it now? Maybe there's just a lag time."

"I'm sympathetic to a more aggressive goal," said glaciologist Jay Zwally of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "The goal that people have adopted of keeping it to a total of two degrees [Celsius] rise since the preindustrial is still going to allow enough warming that we'll have an even more significant impact than we've already seen," he said.

While other scientists agree that 350 ppm is a safer target that increases the likelihood we will avoid many of the negative effects of climate change, some also think it's unrealistic.

"Three hundred and fifty is impossible," said climatologist Stephen Schneider of Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif. "We're going to overshoot 350 and 450 and probably 550, though I sure hope not."

Schneider's hope is that while it might still be 20 years before actions to reduce CO2 emissions really have an effect, innovations over the next two decades will make it possible to dramatically reduce emissions.

"My cynical scenario is that there will be more Katrinas, massive fires, melting of the Arctic, and people will say, 'Oh my God, what have we done. We'd better undo this,'" he said. Such catastrophes could finally spark the dramatic change that's needed, he suggests, if we don't take action sooner of our own accord.

"I try not to talk about a threshold of two degrees," Schneider added. "At 1.8 the world is not fine. At 2.2, we don't turn into a climatic pumpkin. We just have more severe events. The object is not to get hung up on the numbers. The object is to get out there and get solutions."

Others agreed.

Nevermind the Tipping Point

"Time is of the essence here. I don't know if targets like 350 ppm are that useful," said John Harte of the University of California, Berkeley. "We can't make a regulation on something we can't control. We don't regulate temperature, and we don't even regulate the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. However, we control what our automobiles look like. We control the efficiency of our devices. We control what our energy looks like."

"I'm not so enthused about the concept of the tipping point," he added. "My view is that we've probably passed some tipping points. We've entered some realms of irreversibility. There are probably many more, but we don't know where they are."

"We know that if we don't take action, it will be a disaster," he said. "That's all we need to know."

Whether they focused on thresholds or not, the scientists all agreed that the problem is urgent and that not doing anything will lead to disaster: rising sea levels, food shortages, spread of infectious diseases and extinctions.

Starting From Here...

Hansen argued that to achieve the target of 350 ppm, we need to put a moratorium on new coal-fired power plants and phase out burning coal without capturing and storing the carbon.

While scientists agree that coal is a huge part of the problem, they also emphasized the need to apply every available sensible strategy to address the problem.

"There seems to be an emphasis on coal and a distraction from other things we can be doing as well," NASA's Zwally said.

"Some people think that climate change is just about saving a few rare species, and it's just environmentalists making a fuss," Frelich said. "That's really not it."

"It's really about the quality of life for people," he continued. The Earth has been through many big changes before. There have been big extinctions, and new species have evolved to fill the ecosystems. It's not a big deal to the Earth's ecosystems, but it will be a really big deal for the quality of life of humans."

Frelich points out that right now the best soil for growing crops in the United States aligns ideally with the right climate for agriculture. But if the favorable climate moves north, it will be over Canada in an area where bedrock lies at the surface, stripped of soil by the last glaciation.

"If the best climate for growing crops lines up with the Canadian shield, that's an issue for people," he adds.

The scientists also pointed out that countries that tackle this most aggressively will be the winners, regardless of what other nations have committed to.

"The economic giants of the rest of this century are going to be the nations that are selling wind turbines and solar panels and efficient cars to the rest of the world," said Harte. "I would think we'd want to be the leader in that."

"Solving this problem is technologically and economically not that difficult," Harte added. "It's proving to be politically difficult."

credited to Discovery News