It's a nice enough place, this barren dome of rock between Gairloch and Ullapool. Conveniently close to the mainland, like most of Scotland it's not without a certain bleak charm. Just the place for a Heathcliff to do some Wuthering Heights or some Shakespearian witches to stir up a bubbling pot of trouble.

It's a nice enough place, this barren dome of rock between Gairloch and Ullapool. Conveniently close to the mainland, like most of Scotland it's not without a certain bleak charm. Just the place for a Heathcliff to do some Wuthering Heights or some Shakespearian witches to stir up a bubbling pot of trouble.But if you'd landed on its shores just 17 years ago, you would have probably had a very different opinion, one formulated just before you began to suffer something kind of like a cold (high fever, aches, trouble breathing, etc.) and then ... well, how to put it?

You'd die.

Anthrax - For most of the world post-9/11, the word has an immediate stomach punch of frightening recognition. But well before some of it was sent out in envelopes piggybacking the terror of Al-Qaeda, anthrax has been tossed around as a weapon of last resort. There's only one problem when you toss anything around: you just might drop it.

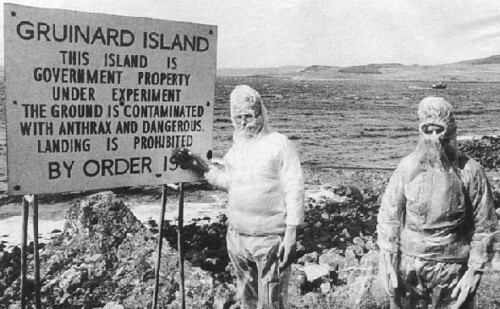

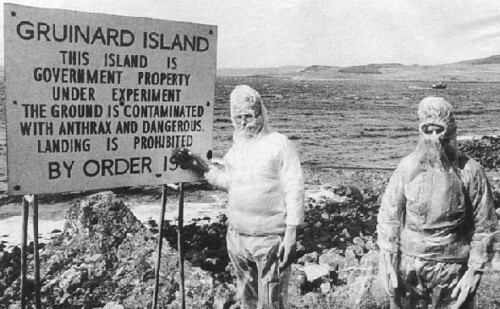

Gruinard Island wasn't an accident, but it could be argued that the testing that took place there in 1942 exceeded the British Government's wildest expectations to a frightening degree. The special breed of anthrax, Vollum 14578l, that was released there via special bombs killed the flock of test sheep within only a few days but had the side effect of leaving that Scottish hunk of rock completely uninhabitable for close to fifty years. In 1990 the island was decontaminated and today it's considered safe for man and beast, though I doubt Gruinard will become a common tourist spot.

Gruinard Island wasn't an accident, but it could be argued that the testing that took place there in 1942 exceeded the British Government's wildest expectations to a frightening degree. The special breed of anthrax, Vollum 14578l, that was released there via special bombs killed the flock of test sheep within only a few days but had the side effect of leaving that Scottish hunk of rock completely uninhabitable for close to fifty years. In 1990 the island was decontaminated and today it's considered safe for man and beast, though I doubt Gruinard will become a common tourist spot.

Once again, Gruinard can't really be considered an "ooops" if the island was intentionally turned into a terrifyingly lethal spot, though that doesn't really make it any easier to think about.

But then there's the town of Sverdlovsk, as it was called back in the days of the USSR (it's now called Ekaterinburg). Lovely little spot, I'm sure, full of all kinds of restfully quiet quaintness and charm, or maybe just the heavy grayness of a typical Soviet town. On a bad day back in 1979, though, Sverdlovsk got even quieter. It was close to a biowarfare lab; one that had an accident.

But then there's the town of Sverdlovsk, as it was called back in the days of the USSR (it's now called Ekaterinburg). Lovely little spot, I'm sure, full of all kinds of restfully quiet quaintness and charm, or maybe just the heavy grayness of a typical Soviet town. On a bad day back in 1979, though, Sverdlovsk got even quieter. It was close to a biowarfare lab; one that had an accident.

What happened to Sverdlovsk wasn't known until 1992 when the KGB finally released its death grip on the info. What came to light was this: because of Soviet slippery fingers, some people died from anthrax exposure. Sixty-eight of them to be precise.

anthrax exposure. Sixty-eight of them to be precise.

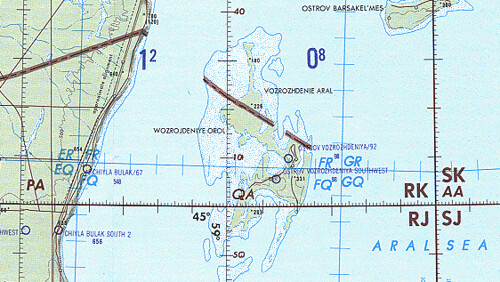

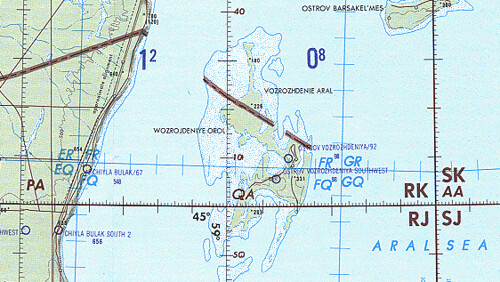

Another scary Russian spot is Vozrozhdeniya Island in the Aral Sea. Ironically meaning "Rebirth," Vozrozhdeniya was used for extensive biowarfare testing. That is until the Soviet Union fell and researchers stationed there decided to walk off the job in 1991, leaving behind anthrax and bubonic plague containers.

Another scary Russian spot is Vozrozhdeniya Island in the Aral Sea. Ironically meaning "Rebirth," Vozrozhdeniya was used for extensive biowarfare testing. That is until the Soviet Union fell and researchers stationed there decided to walk off the job in 1991, leaving behind anthrax and bubonic plague containers.

Bad enough, but what's chilling is that the containers weren't treated with the respect they deserved and many began to [shudder] leak. Vozrozhdeniya was cleaned up in 2002 but between 1991 and 2000, the island was simply

Vozrozhdeniya was cleaned up in 2002 but between 1991 and 2000, the island was simply

posted as a no-go zone. Vozrozhdeniya and Sverdlovsk are scary enough, without getting into the fact that anthrax and bubonic plague can survive for decades even in some very harsh environments, but consider this: we know about Sverdlovsk and Vozrozhdeniya. What about other places we don't know about?

The Japanese against the Chinese in World War II, Iraq versus Iran, Irag against the Kurds, the Holocaust, Germany against the allies in World War I, the Aum Shinrikyo cult against Japan, Russian troops against Chechen terrorists: all kinds of countries and groups have used chemical weapons in battle, or as an attempt at genocide, and what hasn't been used has been developed and stored as forms of chemical and biological Mutual Assured Destruction. In addition to the Russians and the British, we've also conducted more than our fair share of experiments with nasty bugs and chemicals. And although the U.S. hasn't had any accidents -- that we know of -- we've not been particularly careful with these nasties, either.

The Japanese against the Chinese in World War II, Iraq versus Iran, Irag against the Kurds, the Holocaust, Germany against the allies in World War I, the Aum Shinrikyo cult against Japan, Russian troops against Chechen terrorists: all kinds of countries and groups have used chemical weapons in battle, or as an attempt at genocide, and what hasn't been used has been developed and stored as forms of chemical and biological Mutual Assured Destruction. In addition to the Russians and the British, we've also conducted more than our fair share of experiments with nasty bugs and chemicals. And although the U.S. hasn't had any accidents -- that we know of -- we've not been particularly careful with these nasties, either.

While anthrax is frightening because of its longevity and biological spread, for really scary stuff, dig into such delights as Novichok, the v-series, the g-series, and VX. Death in the animal kingdom is one thing, but if you really want to kill, leave it up to our own inventiveness: choking, nausea, salivating, urinating, defecating, gastrointestinal pain, vomiting, then comes the twitching and finally coma. Nerve gas exposure is not a fun way to go.

"The Army now admits that it secretly dumped 64 million pounds of nerve and mustard agents into the sea, along with 400,000 chemical-filled bombs, land mines and rockets and more than 500 tons of radioactive waste - either tossed overboard or packed into the holds of scuttled vessels." ThinkProgress

"The Army now admits that it secretly dumped 64 million pounds of nerve and mustard agents into the sea, along with 400,000 chemical-filled bombs, land mines and rockets and more than 500 tons of radioactive waste - either tossed overboard or packed into the holds of scuttled vessels." ThinkProgress

Bad? Hell yes, but it gets worse. "How can it get worse?" you ask. Well, how about this: we know where about half those sites are. But the rest, because of poor record keeping, are a mystery. Those drums are out there, right now, rusting and no doubt leaking, spilling nasty death into the sea, doing who knows what to crabs and lobsters, fish and ocean flora, and thanks to the food chain, probably even us.

Gruinard Island wasn't an accident, but it could be argued that the testing that took place there in 1942 exceeded the British Government's wildest expectations to a frightening degree. The special breed of anthrax, Vollum 14578l, that was released there via special bombs killed the flock of test sheep within only a few days but had the side effect of leaving that Scottish hunk of rock completely uninhabitable for close to fifty years. In 1990 the island was decontaminated and today it's considered safe for man and beast, though I doubt Gruinard will become a common tourist spot.

Gruinard Island wasn't an accident, but it could be argued that the testing that took place there in 1942 exceeded the British Government's wildest expectations to a frightening degree. The special breed of anthrax, Vollum 14578l, that was released there via special bombs killed the flock of test sheep within only a few days but had the side effect of leaving that Scottish hunk of rock completely uninhabitable for close to fifty years. In 1990 the island was decontaminated and today it's considered safe for man and beast, though I doubt Gruinard will become a common tourist spot.Once again, Gruinard can't really be considered an "ooops" if the island was intentionally turned into a terrifyingly lethal spot, though that doesn't really make it any easier to think about.

But then there's the town of Sverdlovsk, as it was called back in the days of the USSR (it's now called Ekaterinburg). Lovely little spot, I'm sure, full of all kinds of restfully quiet quaintness and charm, or maybe just the heavy grayness of a typical Soviet town. On a bad day back in 1979, though, Sverdlovsk got even quieter. It was close to a biowarfare lab; one that had an accident.

But then there's the town of Sverdlovsk, as it was called back in the days of the USSR (it's now called Ekaterinburg). Lovely little spot, I'm sure, full of all kinds of restfully quiet quaintness and charm, or maybe just the heavy grayness of a typical Soviet town. On a bad day back in 1979, though, Sverdlovsk got even quieter. It was close to a biowarfare lab; one that had an accident.What happened to Sverdlovsk wasn't known until 1992 when the KGB finally released its death grip on the info. What came to light was this: because of Soviet slippery fingers, some people died from

anthrax exposure. Sixty-eight of them to be precise.

anthrax exposure. Sixty-eight of them to be precise. Another scary Russian spot is Vozrozhdeniya Island in the Aral Sea. Ironically meaning "Rebirth," Vozrozhdeniya was used for extensive biowarfare testing. That is until the Soviet Union fell and researchers stationed there decided to walk off the job in 1991, leaving behind anthrax and bubonic plague containers.

Another scary Russian spot is Vozrozhdeniya Island in the Aral Sea. Ironically meaning "Rebirth," Vozrozhdeniya was used for extensive biowarfare testing. That is until the Soviet Union fell and researchers stationed there decided to walk off the job in 1991, leaving behind anthrax and bubonic plague containers.Bad enough, but what's chilling is that the containers weren't treated with the respect they deserved and many began to [shudder] leak.

Vozrozhdeniya was cleaned up in 2002 but between 1991 and 2000, the island was simply

Vozrozhdeniya was cleaned up in 2002 but between 1991 and 2000, the island was simplyposted as a no-go zone. Vozrozhdeniya and Sverdlovsk are scary enough, without getting into the fact that anthrax and bubonic plague can survive for decades even in some very harsh environments, but consider this: we know about Sverdlovsk and Vozrozhdeniya. What about other places we don't know about?

The Japanese against the Chinese in World War II, Iraq versus Iran, Irag against the Kurds, the Holocaust, Germany against the allies in World War I, the Aum Shinrikyo cult against Japan, Russian troops against Chechen terrorists: all kinds of countries and groups have used chemical weapons in battle, or as an attempt at genocide, and what hasn't been used has been developed and stored as forms of chemical and biological Mutual Assured Destruction. In addition to the Russians and the British, we've also conducted more than our fair share of experiments with nasty bugs and chemicals. And although the U.S. hasn't had any accidents -- that we know of -- we've not been particularly careful with these nasties, either.

The Japanese against the Chinese in World War II, Iraq versus Iran, Irag against the Kurds, the Holocaust, Germany against the allies in World War I, the Aum Shinrikyo cult against Japan, Russian troops against Chechen terrorists: all kinds of countries and groups have used chemical weapons in battle, or as an attempt at genocide, and what hasn't been used has been developed and stored as forms of chemical and biological Mutual Assured Destruction. In addition to the Russians and the British, we've also conducted more than our fair share of experiments with nasty bugs and chemicals. And although the U.S. hasn't had any accidents -- that we know of -- we've not been particularly careful with these nasties, either.While anthrax is frightening because of its longevity and biological spread, for really scary stuff, dig into such delights as Novichok, the v-series, the g-series, and VX. Death in the animal kingdom is one thing, but if you really want to kill, leave it up to our own inventiveness: choking, nausea, salivating, urinating, defecating, gastrointestinal pain, vomiting, then comes the twitching and finally coma. Nerve gas exposure is not a fun way to go.

If reading about Vozrozhdeniya and Sverdlovsk leaves a bad taste in the mouth about the way Russia's handled its biological weapons, how about the way the U.S. has handled what could be potentially worse: until 1972 the military basically had carte blanche to dispose of nerve gas agents by dumping them into the ocean. Let's let that sink in for a moment. Nerve and mustard gas -- 64 million tons of it... In the ocean. Not just any ocean, mind you, but in 26 dump sites off the coast of 11 states.

"The Army now admits that it secretly dumped 64 million pounds of nerve and mustard agents into the sea, along with 400,000 chemical-filled bombs, land mines and rockets and more than 500 tons of radioactive waste - either tossed overboard or packed into the holds of scuttled vessels." ThinkProgress

"The Army now admits that it secretly dumped 64 million pounds of nerve and mustard agents into the sea, along with 400,000 chemical-filled bombs, land mines and rockets and more than 500 tons of radioactive waste - either tossed overboard or packed into the holds of scuttled vessels." ThinkProgressBad? Hell yes, but it gets worse. "How can it get worse?" you ask. Well, how about this: we know where about half those sites are. But the rest, because of poor record keeping, are a mystery. Those drums are out there, right now, rusting and no doubt leaking, spilling nasty death into the sea, doing who knows what to crabs and lobsters, fish and ocean flora, and thanks to the food chain, probably even us.

1 comment:

bhopal?

Post a Comment